Exploring deer parks: our oldest and wildest gardens

From art and literature, to royal emblems, to your local pub, the white hart has leapt and gambolled across British history, taking shelter under the ancient trees of deer parks.

As part of our National Gardening Day celebrations, John Fletcher, author of Gardens of Earthly Delight, explores the history of deer parks, explaining why they hold such a special place in his hart.

By John Fletcher | 4 min read

Here in Auchtermuchty on our deer farm it has been so cold and windy, never mind the incessant rain, that National Gardening Day on April 14th seems a little premature. We open our garden for the Scottish Open Gardens Scheme on June 15th/16th and by then it should be awash with wild orchids, azaleas, flowering trees and much else. It is still quite a young garden as we built the house just twelve years ago in a field still grazed by my deer. The upper part is rocky and wild but permeated with grassy paths. It allows me to exercise my passion for propagating the many different species and cultivars of the rowan: very much at home here 500 feet above sea level. And our deer can graze up to the fence and look longingly in from their bare grass pasture.

White Harts

Our deer are all the extremely rare white red deer which we sell as breeding stock. Until Brexit prevented it, we used to sell them to German parks but now we have found a small market in English deer parks which permits me to keep the herd.

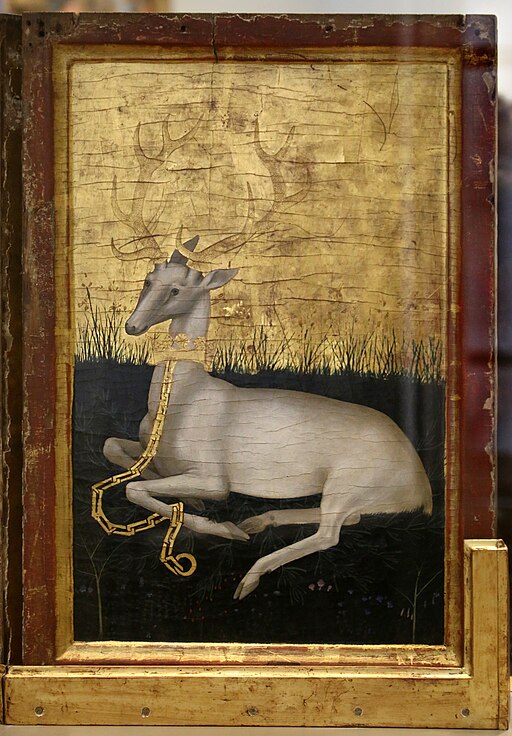

I described in my book, Gardens of Earthly Delight – the History of Deer Parks (Windgather Press: 2011), how white stags provided King Richard II with his emblem of the chained white hart. Since it was Richard who was the first English monarch to license drinking houses, there are still over four hundred British White Hart Inns despite the onslaught of modern pub names. In fact apparently after Red Lions and Royal Oaks the White Hart remains the most popular.

Image credit: National Gallery, CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hart was the medieval name for an adult red deer stag and because of their rarity and the royal obsession with stags, the sighting of a white hart was a matter of great significance. Henry III chased a white hart when he was hunting in Dorset near the little village of King’s Stag. In view of its extreme rarity, he chose to spare it. Thus when a local gentleman, Thomas de la Lynd, subsequently hunted and killed the same stag he attracted royal displeasure and a fine which was exacted on the family every year until the reign of Queen Victoria. Thomas Hardy recounts this tale in Tess of the d’Urbervilles.

The beautiful Wilton Diptych in the National Gallery in London was created as a portable altar piece for King Richard II and is testament to the importance he placed on his white hart emblem. The reverse of one of the two panels is filled by a chained white stag lying on a grassy background whilst on the inside panels all eleven angels and the kneeling monarch himself carry the royal emblem.

The sighting of a white hart was a matter of great significance

In Scotland the appearance of white deer is supposed to portend various events including, on the Isle of Arran, some tragic event in the laird’s family. In 1621 the Earl of Mar recorded the sighting of a white hind on Rannoch Moor to James I who despatched a forester from England to catch it. Unsurprisingly he was unsuccessful. And one of the MacLeod chiefs executed a man for killing a white stag. The legends of white deer permeate cultures throughout Europe and Asia and often feature in foundation myths as, for example, in the founding of Hungary. They are even revered in Japan.

As you can gather I have become rather preoccupied with white red deer. White animals often lead one into dangerous ground. Alice’s white rabbit led her down a burrow and Moby Dick led Ahab to his watery grave. My interest took root when I was researching Gardens of Earthly Delight – the History of Deer Parks.

Gardens or Parks?

I learned a great deal about the foundations of gardening as I wrote that book. The very word ‘park’ shares its origins in Persian words for paradise meaning to be walled around. The Arab philosophy of the paradise garden descends directly from the Iranian paradises with their quartered chahar-bagh. Early hunting reserves were also quadripartite, probably sharing symbolism with the Garden of Eden as described in Genesis: ‘a river went out of Eden to water the gardens and from there it was parted and became four heads.’

In any case, like the medieval secret garden, the Hortus Conclusus, with its connection to roses and the allegory of the Roman de la Rose, was deemed a place of seclusion, tranquillity, and contemplation. The deer park carried the same aura with the addition of its perceived recreational value – historically hunting was, of course, a recreation.

Our deer parks are historical English treasures and ancient wood pastures

Image credit: John Fletcher

The late Oliver Rackham, renowned landscape historian, considered that medieval England had at various times, over three thousand deer parks. Not many of these survive, but we still have more than any other European country and because of this we have more veteran trees as those parks provided protection to ancient trees. The deer benefit from their shelter in winter and their shade in the heat of summer and, in the autumn, they eat the leaves and fruit, the acorns and the nuts which fall.

My book also considered the ha-ha. Many had imagined that the name reflected the way that hiding the sunken fence gave the humorous delusion of an endless lawn. It wasn’t a very funny joke and I learned that more probably the name originated from the Dutch word for a barrier, a haga. To an English ear the Dutch pronunciation of haga is very similar to our ha-ha and provides a much more plausible origin.

I greatly enjoyed writing my book and it provided me with a lot to think about as I hid patiently up trees in ancient deer parks waiting for deer to come close enough for me to dart them with my tranquilliser gun. Our deer parks are historical English treasures and ancient wood pastures. They are our largest and oldest wild gardens.

Featured image: White Hart | Image Credit: John Fletcher

Follow

Follow