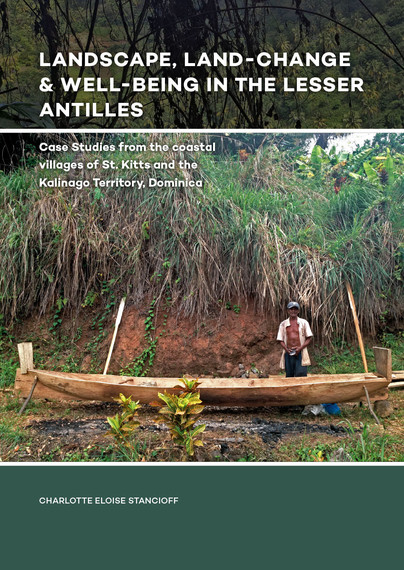

In the Caribbean region, landscape change is part of the region’s history. The Caribbean exemplifies man-made changes to landscape, beginning with Amerindians, continuing to the importation of exotic species through the colony area, extreme land degradation caused by sugar plantation, forced settlement of millions of enslaved Africans, diverse populations of indentured laborers, and continued mixing of cultures from globalized interactions today, such as tourism. This has led to not only intense environmental degradation and introduction of new species, but the fostering of diverse cultures and communities – creating today’s melting pot of environment and community.

Today, the small islands of the Caribbean are often described as vulnerable: with limited resources, growing populations and a dependence on unsustainable economic markets. This perspective often overlooks the adaptability or resilience of these island communities. However, with climate change and intensifying economic connection, landscape change will only increase, bringing not only changes to the ecology but to the customary practices and traditions that play an integral part in the rural community. How do we address these landscape modifications to build more sustainable and equitable land management techniques? This research investigates the changing landscape and land use in two case studies of the coastal villages of St. Kitts and the Kalinago Territory of Dominica. By integrating human and ecological aspects of agrarian landscapes, this research analyzes how land degradation or land change impacts cultural ecosystem services, that ultimately disrupts community wellbeing. First, as a primary goal, the research focus is established together with local communities or stakeholders, identifying both direct and indirect causes of landscape change. Second, by using a variety of qualitative and quantitative methods, but grounded in local participation, the research indicates that landscape change never happens in a vacuum but rather, it is always a part of a larger socio-political context and historical background that must be considered. In both case studies, there remains emphasis on the tangible, as results not only lead to new directions in landscape research but also deliverables used by community stakeholders for continued land sustainability. By investigating the synergies of nature and community within landscape change, this research proposes that local communities assert their own agency. This moves away from how local communities fit into global phenomena of land change, to how communities can assert their diversity within a global process.